‘J’ is for Trust: How Labour’s Comms Strategy Turned it Around for Starmer

Kier Starmer seems happy to be known as the ‘Boring One’ and this safe pair of hands are rebuilding trust in both the Labour party and our political system one brick at a time.

Kier Starmer reminds me of Jurgen Klopp, introducing himself as the ‘Normal One’ at his inaugural press conference as Liverpool manager in 2015.

Jurgen was defining himself in contrast to the then Chelsea Manager, Jose Mourinho — ‘the Special One’. When Sir Kier became party leader he also had to distinguish himself from the leader of the blue team. Whilst Boris Johnson and Jose Mourinho grabbed the headlines, they ultimately inspired the demise of their respective clubs.

Klopp, on the other hand, went on to inspire hope not only for the Reds, but for the wider city beyond football, at a time of general despondency. Can Kier do the same?

Granted, Kier does not have the charisma that Jurgen had, but if charisma was the Liverpool Manager’s only superpower he wouldn’t have won the accolades he did. Jurgen knew what the people wanted, he connected with the heart of the city, and he wasn’t afraid to make difficult decisions to get to where he wanted to go.

The J-Curve

J isn’t just for Jurgen.

The J-curve, an economic model co-opted by political scientist J. C. Davies to explain political revolutions, was introduced to Kier Starmer by Labour campaign director, Morgan McSweeney in 2020. It became central to Sir Kier’s campaign strategy and eventual rise in popularity.

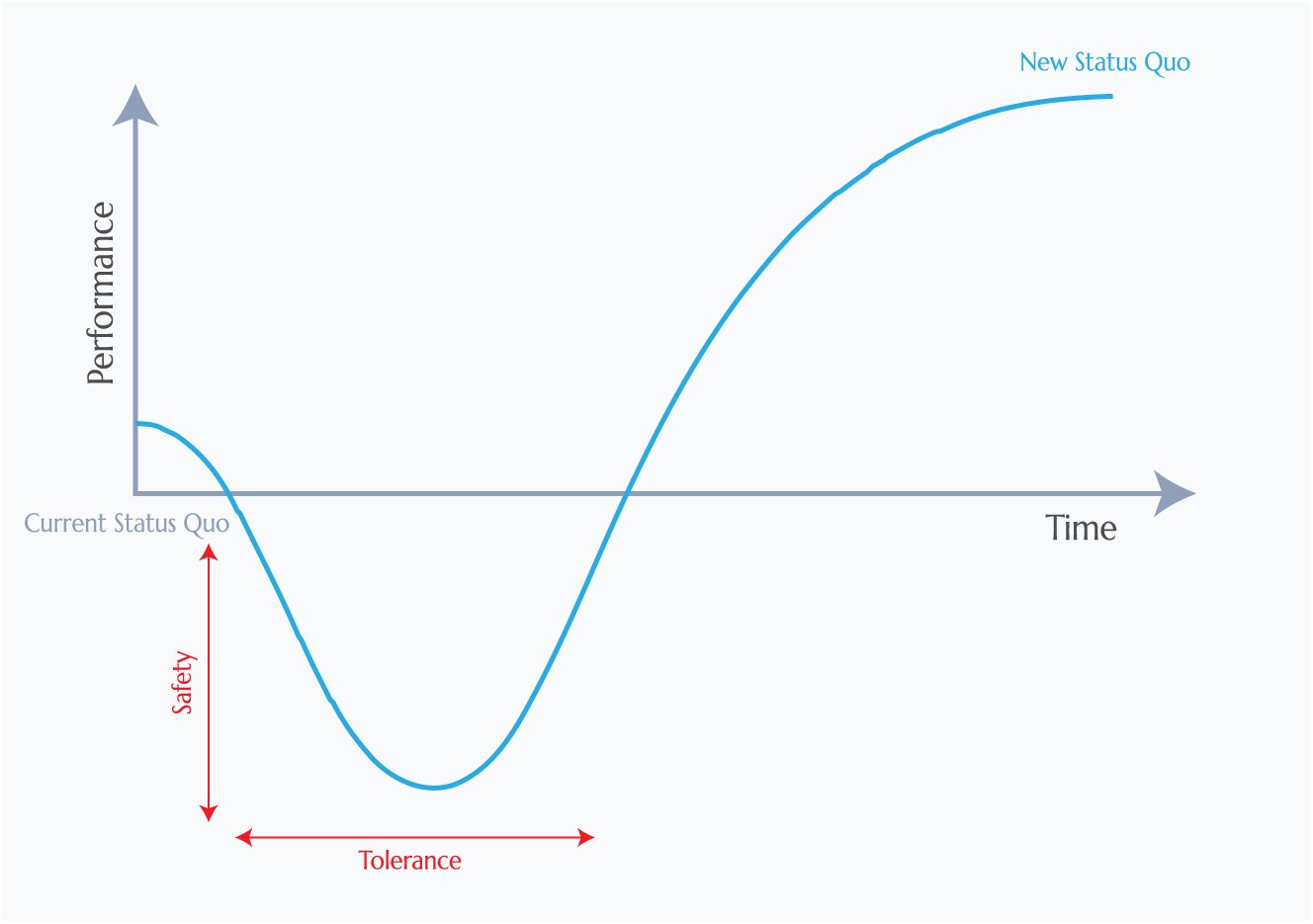

The curve gets its J shape by tracing ‘performance’ over time. From the status quo, the line dips for a moment, before rising to a new level. It shows that change requires sacrifice; that things have to get worse before they can get better.

From the outset, Team Starmer prepared themselves to make difficult decisions in order to put the red house in order. Braced for an unknown period of unpopularity, McSweeney’s internal strategy memorandum ‘Labour for the Country’ warned that Labour needed visible transformation to break from the past - Sir Kier needed to be brutal.

So what can we learn from the J curve?

Take responsibility and take action

In his nine-page document Morgan McSweeney wrote, ‘The Government is clearly benefiting at the moment from the goodwill generated by the vaccine. However, we should not take cover in this position: there is no evidence that without it we would be in a very different place from where we are now, and we must take responsibility for that.’

‘We must change more profoundly than we have accepted until now, we must embrace the conflict that is inevitable, and we must show the public that our vision is something worth fighting for’, read the memo.

Focus on the needs of real people, not Twitter people

The strategist went on to complain that too many of the party leadership’s discussions were dominated by ‘statues in Bristol, Meghan Markle’s struggles with the Royal Family or the number of union flags in our zoom interviews’, pointing out that none of these issues had any real relevance for people’s primary concerns: ‘jobs, livelihoods, crime and public services’.

He wrote that the party seemed to be ‘lost in a Twitter-driven comfort zone of its own’ more willing to listen to ‘the self-identifying legions of people who inhabit social media than the voters we need to attract away from Johnson’s coalition’.

Unity is not built by looking inwards

Inheriting a party riddled by division, Starmer made clear in his leadership campaign that his priority would be ‘unity’. But McSweeney’s response to this was that ‘prizing unity above all else leads us to look inwards and away from our voters. We overvalue its importance and this …shrinks our electoral appeal’. The true objective should be to show that Labour was ‘no longer only focussed on itself’ but ‘on the real world of people’s everyday hopes and fears’.

Party divisions have been laid bear in recent weeks with public spats over the candidacies of Jeremy Corbyn and Diane Abbott and accusations of a broader “cull” of left wing candidates. However, Sir Kier’s approval rating by Labour supporters is up to 55% according to YouGov - compared with Jeremy Corbyn’s 18% in the aftermath of the 2019 election.

Furthermore, a poll released last week (10 June 2024) suggests that 36% of the general population feel that Kier Starmer respects ‘people like you’ compared to 24% for Jeremy Corbyn and 19% for Rishi Sunak. This significant metric is a proxy for trust and shows that the J-Curve playbook is working.

Kier Starmer’s approval ratings aren’t spectacular, but it so happens that the public isn’t looking for spectacles this time around. As More In Common’s research suggests, currently ‘‘showing respect to ordinary people’ is the most important attribute that the public want in a politician - even above having new ideas and getting things done.’ This is a good sign that Labour’s uptick isn’t solely down to the Tory demise.

It seems obvious to us ‘normal ones’ that approval comes from understanding everyday people’s needs and desires. But we also know that parties are loud and the music often drowns out the noise of the crowd. Spend long enough inside the club and you can easily forget that the outside world exists. Instead you find yourself obsessing over who kissed who on the dancefloor and who’s got the killer moves. Whilst the Tories lick their wounds, it seems that Labour’s decision to take responsibility and look beyond their base is paying off.