Finally, a Politician with a Comms Campaign Based on Listening…

Budgets are being slashed and whole creative teams are getting dropped at many of the organisations that I work with. The comforting news is that the staple, expensive, old style of communication is out, and there’s a new, more cost effective, more engaging approach on the scene.

Budgets are being slashed and whole creative teams are getting dropped at many of the organisations that I work with. The comforting news is that the staple, expensive, old style of communication is out, and there’s a new, more cost effective, more engaging approach on the scene.

Without dismissing the very real challenges people and organisations are facing, this shake-up across the Aid, Government, and Private sectors is also an opportunity — to radically transform how we communicate with the public. The good news is: the leaner way is now also the more effective one.

This week, in a major upset, fresh-faced Zohran Mamdani beat establishment heavyweight Andrew Cuomo in the primaries to become the Democrats’ mayoral candidate for New York. A campaign built on listening, not shouting. It was cheaper, bolder, and far more memorable.

It’s an ‘I told you so’ week for us at Liike. As political commentator Chris Hayes put it:

‘So many politicians communicate by focusing on what they’re telling you. But what was fascinating about Mamdani’s campaign is that he turned the act of listening into a form of broadcasting.’

We’ve been calling it for a while and now the revolution in political communication is about to begin. Campaigns that put people at the centre, that listen and serve, don’t just feel better — they perform better. They generate more compelling content, more emotional connection, and far less need for expensive TV slots or billboard campaigns.

Here are five things I’ve learned from Mamdani’s masterclass in campaigning:

1. Listening is Messaging

Instead of blitzing audiences with slogans, Mamdani’s team treated listening as a campaign strategy. The approach made supporters feel heard, sharpened the campaign’s resonance and showed dialogue and deliberation as core leadership strengths.

2. Go Deep, Not Wide

Rather than spending millions on mass media, Mamdani’s campaign focused on deeply engaging communities through relational organising and hyperlocal storytelling. A smaller, committed audience that feels ownership beats a larger, passive one.

3. Content as Mobilisation, Not Just Messaging

Every video, reel, and leaflet wasn’t just informative — it carried a call to action. Design your content to move people, not just inform them. Action is the most powerful metric of engagement.

4. Platform Native

Mamdani’s social native campaign leaned into a raw, unvarnished aesthetic — phone-shot videos, earnest voice notes, real-time updates. It made him feel more human, and his message more trustworthy. But he had to have team members fluent in Tiktok to do so.

5. Mimetic Messaging

Your policy points must be relevant, memorable and repeatable. Successful communication is rooted in the art of listening to people, generating relevant, practical policy ideas and distilling them down into simple slogans and phrases: short, sticky and values-driven.

Reflecting on Cuomo’s humiliating loss, Democratic Strategist, Amit Singh Bagga, reflected:

‘The establishment, at this point, is suicidally clinging to a version of power it no longer even has. We have made this choice to not evolve – and if you do not evolve, you will walk your party – and potentially our democracy – up to the brink of extinction.’

The message is clear: if our leaders continue to centre themselves — not the people they serve — public disengagement and political extremism will only grow.

Budgets are being slashed and whole creative teams are getting dropped from many of the organisations that we work with. But we’re hearing from our clients that a lot of the content we’ve produced is outperforming others. We put that down to our people-centred approach.

If you’re looking to engage more deeply, spend less, and communicate better — Liike is here to help.

Always listen to your Mum.

"This is painful in a way that we can't forget" - Mariam

In 2022 we got to sit with four amazing women who had travelled to Juba from four conflicting tribal communities to tell us about their stories of loss. They wanted to communicate a message of peace to their respective communities in a way that might cut through.

We released the trailer for our new film for Peace Canal yesterday, as the start to a special campaign against armed violence in South Sudan.

"This is painful in a way that we can't forget" - Mariam

In 2022 we got to sit with four amazing women who had travelled to Juba from four conflicting tribal communities to tell us about their stories of loss. They wanted to communicate a message of peace to their respective communities in a way that might cut through.

If anything's going to get you, it's seeing your mum cry.

Violence and cattle raiding is a way of life for many young men in pastoralist communities in South Sudan, and it's encouraged and perpetuated by many external vested interests. But we hope that this film will make some think about the consequences of violence and see that there's another way to live.

We’re pushing this campaign out through WhatsApp and Facebook groups, which are the most popular channels amongst diaspora and pastoralist communities. Even cattle camp youth leaders often have phones, hooked up to solar powered chargers, watching Nollywood films in a huddle with the other kids.

There’s a wise saying that holds true in every culture - ‘Listen to your mum’. We hope that these guys will.

How to Choose the Right Editor for the Job

A few years ago I hired an editor for a first time job with a new government agency client. I was still very green, and I wanted to impress. It was a film about sexual exploitation and required a mix of footage and motion graphics. I briefed the editor: 'Make it emotive. We need to motivate people to make a change.'

It was a very last minute commission and we were running out of time. On deadline day the editor turned in the edit. It was bad.

A few years ago I hired an editor for a first time job with a new government agency client. I was still very green, and I wanted to impress. It was a film about sexual exploitation and required a mix of footage and motion graphics. I briefed the editor: 'Make it emotive. We need to motivate people to make a change.'

It was a very last minute commission and we were running out of time. On deadline day the editor turned in the edit. It was bad. At the start of the video, he'd arranged the text to look like a pair of knickers. I questioned him about his creative decision making. 'I wanted to humanise the data' was the response.

Some editors are artists and some are technicians. There's a time and a place for both.

For the last (nearly) five years I've had the big privilege of running a network of freelancers called Freelance Union — FU for short — a now 650 member strong group of talented film, TV and creative professionals. The 'Union' also gives us at Liike the ability to build the right crew for the right job.

Here are my hot tips if you're looking for the right editor or film crew for a project:

Write a clear brief, including a summary of deliverables, for which platforms and which target audience.

Include visual references from videos that you want to emulate (copying isn't illegal, immoral or unprofessional)

If you don't know what you want or need, be honest about that and have a conversation. Most of us creatives prefer being given problems to solve, rather than guessed-up solutions.

Ask the editor/producer for examples of work they've done in a similar style/genre. And ask what their role/responsibilities were in the making of those examples.

Ask for a post-production timeline, when they'll need your feedback and how many rounds of amends you get in the quoted price. Communication and time-keeping is as important as talent.

If you want to change hearts and minds or connect with audiences on a deeper level through human storytelling, talk to us. We sacked the old editor and I'm less green these days.

‘J’ is for Trust: How Labour’s Comms Strategy Turned it Around for Starmer

Kier Starmer seems happy to be known as the ‘Boring One’ and this safe pair of hands are rebuilding trust in both the Labour party and our political system one brick at a time.

Kier Starmer seems happy to be known as the ‘Boring One’ and this safe pair of hands are rebuilding trust in both the Labour party and our political system one brick at a time.

Kier Starmer reminds me of Jurgen Klopp, introducing himself as the ‘Normal One’ at his inaugural press conference as Liverpool manager in 2015.

Jurgen was defining himself in contrast to the then Chelsea Manager, Jose Mourinho — ‘the Special One’. When Sir Kier became party leader he also had to distinguish himself from the leader of the blue team. Whilst Boris Johnson and Jose Mourinho grabbed the headlines, they ultimately inspired the demise of their respective clubs.

Klopp, on the other hand, went on to inspire hope not only for the Reds, but for the wider city beyond football, at a time of general despondency. Can Kier do the same?

Granted, Kier does not have the charisma that Jurgen had, but if charisma was the Liverpool Manager’s only superpower he wouldn’t have won the accolades he did. Jurgen knew what the people wanted, he connected with the heart of the city, and he wasn’t afraid to make difficult decisions to get to where he wanted to go.

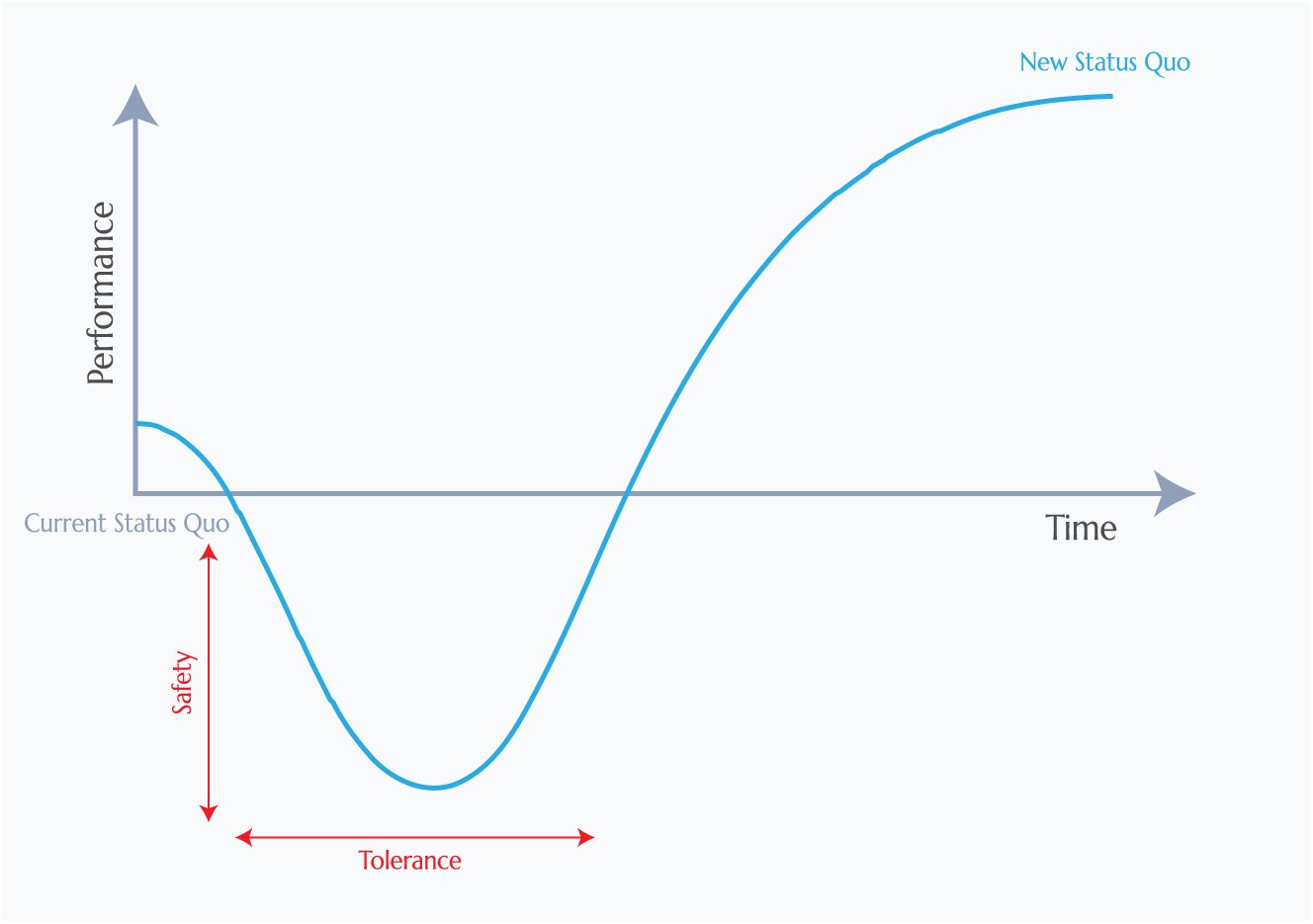

The J-Curve

J isn’t just for Jurgen.

The J-curve, an economic model co-opted by political scientist J. C. Davies to explain political revolutions, was introduced to Kier Starmer by Labour campaign director, Morgan McSweeney in 2020. It became central to Sir Kier’s campaign strategy and eventual rise in popularity.

The curve gets its J shape by tracing ‘performance’ over time. From the status quo, the line dips for a moment, before rising to a new level. It shows that change requires sacrifice; that things have to get worse before they can get better.

From the outset, Team Starmer prepared themselves to make difficult decisions in order to put the red house in order. Braced for an unknown period of unpopularity, McSweeney’s internal strategy memorandum ‘Labour for the Country’ warned that Labour needed visible transformation to break from the past - Sir Kier needed to be brutal.

So what can we learn from the J curve?

Take responsibility and take action

In his nine-page document Morgan McSweeney wrote, ‘The Government is clearly benefiting at the moment from the goodwill generated by the vaccine. However, we should not take cover in this position: there is no evidence that without it we would be in a very different place from where we are now, and we must take responsibility for that.’

‘We must change more profoundly than we have accepted until now, we must embrace the conflict that is inevitable, and we must show the public that our vision is something worth fighting for’, read the memo.

Focus on the needs of real people, not Twitter people

The strategist went on to complain that too many of the party leadership’s discussions were dominated by ‘statues in Bristol, Meghan Markle’s struggles with the Royal Family or the number of union flags in our zoom interviews’, pointing out that none of these issues had any real relevance for people’s primary concerns: ‘jobs, livelihoods, crime and public services’.

He wrote that the party seemed to be ‘lost in a Twitter-driven comfort zone of its own’ more willing to listen to ‘the self-identifying legions of people who inhabit social media than the voters we need to attract away from Johnson’s coalition’.

Unity is not built by looking inwards

Inheriting a party riddled by division, Starmer made clear in his leadership campaign that his priority would be ‘unity’. But McSweeney’s response to this was that ‘prizing unity above all else leads us to look inwards and away from our voters. We overvalue its importance and this …shrinks our electoral appeal’. The true objective should be to show that Labour was ‘no longer only focussed on itself’ but ‘on the real world of people’s everyday hopes and fears’.

Party divisions have been laid bear in recent weeks with public spats over the candidacies of Jeremy Corbyn and Diane Abbott and accusations of a broader “cull” of left wing candidates. However, Sir Kier’s approval rating by Labour supporters is up to 55% according to YouGov - compared with Jeremy Corbyn’s 18% in the aftermath of the 2019 election.

Furthermore, a poll released last week (10 June 2024) suggests that 36% of the general population feel that Kier Starmer respects ‘people like you’ compared to 24% for Jeremy Corbyn and 19% for Rishi Sunak. This significant metric is a proxy for trust and shows that the J-Curve playbook is working.

Kier Starmer’s approval ratings aren’t spectacular, but it so happens that the public isn’t looking for spectacles this time around. As More In Common’s research suggests, currently ‘‘showing respect to ordinary people’ is the most important attribute that the public want in a politician - even above having new ideas and getting things done.’ This is a good sign that Labour’s uptick isn’t solely down to the Tory demise.

It seems obvious to us ‘normal ones’ that approval comes from understanding everyday people’s needs and desires. But we also know that parties are loud and the music often drowns out the noise of the crowd. Spend long enough inside the club and you can easily forget that the outside world exists. Instead you find yourself obsessing over who kissed who on the dancefloor and who’s got the killer moves. Whilst the Tories lick their wounds, it seems that Labour’s decision to take responsibility and look beyond their base is paying off.

Unless you Involve Women There will be no Peace: An Interview with Christine Kide.

‘Whenever you fight, we are the ones who suffer. We are the ones who who are battling the pain of of losing a loved one. We are the ones losing resources and we are the ones coming to struggle with the families after the conflict. So we as we are the centre of this struggle, …and no one wants to stop the conflict.’

I had the chance to sit down with Peace Canal’s Executive Director, Christine Kide, to learn about the unique role that women have to play in peacebuilding amongst the pastoralist communities in South Sudan.

Peace Canal is a South Sudanese NGO that I work with in my role as Communications Lead for the Peace Opportunities Fund. Our mission is to establish sustainable national NGOs in the country, because locals know best.

Here’s the interview:

Jonty: So, Christine, let's start by finding out a bit about yourself and how you got involved with Peace Canal to begin with.

Christine: It's something that, every time I reflect on it, I think it's an experience worth sharing to inspire the women in South Sudan to go way beyond their capabilities or to dream bigger than they think they can.

I applied for it with very little expectation because I knew it was a competitive position.

I made it through as the Executive Director! I couldn't believe it, but here I am. My thoughts about myself changed, and I felt like if I could dream and become what I dreamt of, then anyone out there can dream and become what they wish to be.

At that time, Peace Canal was, and still is, a male-dominated institution. The male domination isn't because it's not working with women or doesn't want to work with women, but because of the circumstances surrounding the kind of work Peace Canal does and the locations they engage with communities.

We engage directly with youth involved in conflict and face challenges with male-dominated societal structures. Traditions often don't expect women to engage in community peacebuilding initiatives, but we're seeing a slight shift. Since I took up this role, I've ensured to engage directly with these community leaders, and we've seen a shift in their willingness to work with women.

Meeting the spiritual leader, Da Kueth, and other key figures has shown that my role is shifting mindsets towards women in decision-making. The communities have been supportive, and this has been a significant part of my journey. So yeah, it's been a whole lot of a process and I think, we are, we are moving towards that shift.

Jonty: So, the brave step you took to apply for this role and to believe you could lead this organisation in a male-dominated sector has been an inspiration to women across communities in South Sudan. That's amazing. I wanted to ask about some of the acute challenges that women face in conflict communities in South Sudan because they experience conflict in a different way don’t they? Tell us a bit about that.

Christine: In most cases women have been used as a weapon of war when they are abducted, they are raped. They are, you know, forced into marriages…

At the same time, gender stereotypes restrict women in engaging in decision making, restrict women from dreaming and working with their communities closely, trying to cause a change in their communities. We have made it known to the communities that if we are discussing community issues, everyone has to be engaged, the women have to be there, the youth have to be there, the chiefs have to be there and the authorities have to be there.

Women bear the burden of conflict because they are the most affected. They lose children, husbands, relatives, and resources, and are often left vulnerable. In the recovery process, they take on the responsibility of managing families and providing for them. This is one reason women are at the forefront of championing peace in the communities we work with. They understand their pain and want to put an end to the conflict.

Women are trying their best to ensure they live in a peaceful environment, but it's still a challenge. They battle many things, including gender-based violence, child marriage, and harmful cultural practices, in addition to inter-communal conflicts and cattle raids. These challenges inspire them to champion peace. It's true that conflict affects people differently, and bringing women to the table of peace discussions sends a signal that their voices matter.

In 2020, the Peace Opportunities Fund worked with the Dinka Agar community to address internal conflict between different clans, and established ‘Akut de Door’ peace committees where they could air the grievances and find ways forward towards working together again.

One key achievement was having women represented in the Akut de Door peace committee structures in Lakes State because these structures was specifically established, for the the cattle camp youth leaders and we engaged the cattle camp youth leaders to sensitise them on the importance of having women in these structures which they agreed.

So they have now accepted to have at least a woman representative in all the peace committees for the cattle camp youth leadership and so we have been able to see that now women are having conversations about their needs.

Also the role of the women traditionally has been to create songs that incites the youth to go and fight, and they would also brew alcohol and offer them the alcohol so that when they are going to fight they are drunk, so they can make decisions to go and fight the other communities.

But after sitting down with the communities, the youth were able to tell them, ‘But look, you are the ones who composed these songs to incite us to go and fight.’ So the women started looking at the role they are playing in conflict.

So in Lakes State the women said, ‘Okay, so what should we do to stop this?’ So first of all, they agreed that they will not be brewing alcohol anymore for the youth, and whoever brews alcohol to sell to the youth will be reported to the authorities and arrested. Then also they decided to, instead of composing harmful songs or inciteful songs they composed, they started composing peaceful songs that they can sing to cheer their youth, and to also share information on peace with each others community.

Christine told me that the Akut de Door have been a ‘game changer’ in Lakes State and that there have been no significant conflicts within the Dinka Agar community since.

Christine: And so, because youths became peaceful with each other, they had to ask us like, ‘Okay, so now we have peace, but what are we going to eat? Because when we used to go and raid we will find cattle, we get resources for ourselves.’’

Peace Canal has now worked with the local government to establish five ‘peace farms’ with the Dinka Agar community to provide livelihoods for the community.

Jonty: I'd love to hear more about the unique challenges women face and their potential as a force for peace in their communities.

Christine: Women are now getting to know their worth and understanding their capabilities. They are searching for opportunities to lead and be heard. For example, in our Annual Cattle Camp Migration Conference, women were not initially well represented, but now they are fully a stakeholder group. We find that women now are bold enough to bring issues like child marriage into the discussions. And they have been clearly pointing out how they are struggling with the fact that their children are abducted, saying ‘Whenever you fight, we are the ones who suffer. We are the ones who who are battling the pain of of losing a loved one. We are the ones losing resources and we are the ones coming to struggle with the families after the conflict. So we as we are the center of this struggle, …and no one wants to stop the conflict.’ So I think they've have the confidence to tell their communities that this is our problem.

‘Whenever you fight, we are the ones who suffer. We are the ones who who are battling the pain of of losing a loved one. We are the ones losing resources and we are the ones coming to struggle with the families after the conflict.’

We are moving towards a society where women's voices are respected in decision-making processes. They are starting to believe that involving women in these discussions can lead to better solutions.

The Intercommunal Governance Structures (ICGS) are a series of dialogues also established by the Peace Opportunities Fund in partnership with the Lou, Nuer, Dinka Agar and Murle communities in 2020, and subsequently supported by Peace Canal.

Christine: The most important this is that these women [from the conflicting communities], have been able to establish a relationship among themselves [through the ICGS]. They have been able to build trust so that when there is a mobilization, for example, in the community of GPAA, the women in GPAA will call their counterparts in the Dinka communities in Jonglei and also the Nuer communities and tell them, 'Our youth are mobilizing, so be ready to move far so that they don't find you here’. There was an incident that happened early this year - there were rumours of an attack in Duk. So there was communication from GPAA to Jonglei and, the communities mobilised themselves to make sure that the women, the children were moved very far away from the cattle camps. And when the attack happened, there was not much casualty. No women abduction, no children abduction.

They have been asking us, requesting that we provide them with sattelite phones because there are some places that have limited connectivity, so that they can be frequently communicating with each other well. I have found support through different partners, so we are procuring at least one per county.

Jonty: Where do you hope to see the role of women in peacebuilding in the next ten years?

Christine: I have a strong feeling that if it's left for women, we will not need the ten years to ensure that we have peace in these communities.

I think the women were looking at the losses they are getting as a community because of the fights. They will think about their children, they'll think about their husbands, they'll think about their relatives, they'll think about accessibility to services and opportunities, which I think the youth do not look at.

I think [they] have the passion, they have the energy, and they have that vision of living in a peaceful community because with peace, they know they can achieve a lot in a peaceful society.

We are also hoping to to establish, a women's circle for for the Murle, Dinka and the Nuer women because they want to work together they want to build trust among themselves because they feel that if they build this trust among themselves, their youth will not attack the other communities. The youth will not fight each other because they know their mothers, their sisters are working together to survive, you know?

How to Write a Shared Vision Statement with a Roomful of People from Warring Tribal Backgrounds

With all of the belly laughter and back slapping it’s easy to forget that everyone in the room has been affected by the ongoing tribal war, on different sides. Those in attendance make up (most of) Peace Canal’s peacebuilding team, drawn together from the Nuer, Dinka and Murle communities of Lakes State and Jonglei-GPAA in South Sudan.

With all of the belly laughter and back slapping it’s easy to forget that everyone in the room has been affected by the ongoing tribal war, on different sides. Those in attendance make up (most of) Peace Canal’s peacebuilding team, drawn together from the Nuer, Dinka and Murle communities of Lakes State and Jonglei-GPAA in South Sudan.

The saying goes that too many cooks spoil the broth, and there was certainly a kitchen-like heat in the room on this sticky Juba day, at the threshold of rainy season. We had come together to cook up a Vision, Mission and Values statement for Peace Canal - eleven of the sixteen-strong team, plus myself and Rob Lancaster as support from the Peace Opportunities Fund. The challenge: to consolidate all of this energy, enthusiasm, expertise and experience into three short paragraphs. Even for a roomful of seasoned facilitators this was going to be a test, but here is how we went about it…

Step one. Appreciative Enquiry

‘In pairs, take it in turns to tell each other about a time when you’ve felt most energised by your work with Peace Canal. Think about the conditions that enabled that, and what you valued about your contribution and about Peace Canal in that situation. Finally think about one thing that, if it were missing, would make Peace Canal a completely different organisation.’

Unleash the stories - trekking into the bush for days on foot, encountering lions to bring warring groups together for the first time; loading armed youth leaders onto aeroplanes; walking through unknown territory to connect with the chiefs from other tribes…

What, How, Who, Why

‘Based on the stories you’ve shared with each other, note down: what does Peace Canal do best; how does Peace Canal do those things, who is involved, and why do you do them.’

We talked about the ICGS - the Inter-Communal Governance Structures - which was established by local communities in partnership with Peace Canal and helped to soothe a swell of support for revenge killings; about the process of building Peace Canal’s own diverse team; about the ‘Youth Caravan’ which took armed youth leaders on tour to meet other, rival communities face to face. The room was alive as we reconnected with all that Peace Canal has done to help communities establish greater levels of peace and security, over the last four years.

Distillation

Having discussed the What, How, Who and Why’s as a whole, groups of three were then tasked with consolidating each element.

Peace Canal is stratified, but this was a democratic process, so the responsibility for leading each group was dished out at random, not by rank - an important detail to ensure inclusivity and buy-in on every level.

The groups rotated, giving feedback on each others’ summaries, before sharing a final statement with the room.

There were objections but, using a ‘consent based process’ we landed on a shared statement with only three minor tweaks. One very useful tool in the process was the question, ‘Can you live with this?’. Perfection is the enemy of consensus. Aim for something functional, not flawless; a description, not a definition.

Symbols

As the day’s caffeine set in dark circles under our eyes, the final task of the afternoon was to come up with 2-3 symbols that represent Peace Canal’s values. Why symbols?

Four reasons:

they’re more memorable

they’re richer in meaning

more distinctive

and easier for people to personalise than abstract buzzwords like ‘peace’, ‘community’ or ‘sustainable’.

Our minds had cut a little loose by 4pm, but the group came up with two profound metaphors, which I was still digesting over breakfast with Rob the next morning.

You might not get the meaning at first, but once I explain them I bet you won’t forget them. The group came up with two sketches…

A tree with outstretched branches reaching over contested arable land, offering shade to those who desire rest and resolution.

A pair of canoe oars that propel and steer the boat through the waters, towards its destination.

Peace Canal is like the tree, creating the environment for all to come to find peace. The tree can’t enforce peace upon anyone - that is up to the communities themselves. Nor can the tree make the communities want to meet in the first place, but her shadow is inviting and as patient as the scorching sun that hangs in the sky.

Peace Canal is like the pair of oars. The water, like peace, is an enabling environment, allowing the boat - the communities - to reach their destination together. Crucially, the canoe only finds its way with the direction and guidance of those doing the paddling - the communities themselves.

What could have ended up as a mess - where certain opinions and perspectives dominated - resulted in more back slapping, belly laughter and an organisation with a renewed sense of focus.

Why won’t you DEI?

How do you make people change their attitudes and behaviours without them ending up resenting you?…

More in Common released an interesting report on Saturday, on Equity, Diversity and Inclusion, whether people really are fed up of it, and how we can communicate it in a way that works.

Campaign design is the art of pairing human experience with data, and my friends at More in Common are positively ‘Heston Blumenthal’ in how they do just that.

‘Finding a Balance - How to ensure Equality, Diversity and Inclusion is for everyone’ had my lips smacking as I devoured the report on the train this morning. EDI is a topic that pervades a lot of our communications work and is a dynamic that flavours daily life for a lot of my friends and loved-ones.

Bitter and sweet.

How do you make people change their attitudes and behaviours without them ending up resenting you?…

More in Common released an interesting report on Saturday, on Equity, Diversity and Inclusion, whether people really are fed up of it, and how we can communicate it in a way that works.

Campaign design is the art of pairing human experience with data, and my friends at More in Common are positively ‘Heston Blumenthal’ in how they do just that.

‘Finding a Balance - How to ensure Equality, Diversity and Inclusion is for everyone’ had my lips smacking as I devoured the report on the train this morning. EDI is a topic that pervades a lot of our communications work and is a dynamic that flavours daily life for a lot of my friends and loved-ones.

Bitter and sweet.

It’s often communicated badly, can ironically divide people rather than include them, and it’s the subject of noisy, often dehumanising, op-ed columns and X-rants. Today’s report shows that 73% of the UK feel that people are often or sometimes made to feel stupid for not understanding the latest way to talk about diversity issues.

But the research - done in partnership with Oxford University - offers helpful proof that there is still an appetite for DEI (thank God, we’re not yet so inhumane) and there is indeed a way to do it well (sweet relief!).

In summary, here’s what I’ve taken from it:

How to communicate DEI badly:

Be unbothered - it’s just a tick-box exercise after all

Be impractical and don’t think about context - don’t tailor DEI activities to your specific job or institution, or anything relevant to people’s everyday experiences

Rant at people and punish them for being wrong - use aggressive and polarising language that creates an 'us vs them' dynamic

How to communicate DEI successfully:

Listen to people, understand real-world experiences and share stories - ground DEI comms in the context of people's everyday lives and work

Be honest, human and curious - encourage a culture of curiosity and agree a way of responding to mistakes graciously that doesn’t involve public shaming

Focus on the whole - Celebrate everyone’s uniqueness and show how DEI benefits us all

Focus on shared values - Link DEI to fairness, merit, and reducing barriers to opportunity

Reading this report this morning was another reminder that real life is so much more hopeful than X-life. Thanks More in Common!

I also feel emboldened in our mission to keep making public communication more human and to continue to follow our campaign design habits: understand what people really want; communicate locally; tell stories.

If you’re struggling to DEI successfully, let’s chat…

Read More in Common’s report here: moreincommon.org.uk/our-work/research/finding-a-balance/

To make peace, bring the fighters together

I’ve just returned from two weeks in South Sudan, spending time with representatives from warring tribal groups from some of the most violent parts of the country. I am inspired.

These representatives make up Peace Canal - an organisation that’s working to put an end to organised violence in Africa’s poorest nation.

We’ve recently been appointed to support Peace Canal with their strategic communications, so my last two weeks have been spent getting a thorough orientation from my new colleagues…

I’ve just returned from two weeks in South Sudan, spending time with representatives from warring tribal groups from some of the most violent parts of the country. I am inspired.

These representatives make up Peace Canal - an organisation that’s working to put an end to organised violence in Africa’s poorest nation.

We’ve recently been appointed to support Peace Canal with their strategic communications, so my last two weeks have been spent getting a thorough orientation from my new colleagues:

Unlike other NGOs that were dealing with secondary actors, Peace Canal was dealing with primary actors of conflict.

- Gordon Majuec Ayen, Area Coordinator for Greater Rumbek

Peace Canal works in a unique way with the communities by engaging those directly involved in conflict and in most cases it looks to be a risky venture that we take to look for those who are directly engaging with conflict.

- Christine Kide, Executive Director

Where much peacebuilding work is focussed on security at a national level (which is important), Peace Canal go directly to the communities, meet with armed leaders, seek to understand their needs and encourage them to meet with their opposition.

One approach to peace holds people back from each other, the other brings them back together.

One approach empowers government and security forces, the other empowers communities.

One approach comes with solutions, the other creates the space for solutions to emerge.

This upside-down way of doing things seems to be effective.

Since Peace Canal started working in areas of Jonglei and GPAA we have seen a systematic reduction in violence and communal attacks.

- Christine

One of Peace Canal’s superpowers is that they have skin in the game. All of our fieldworkers are recruited directly from the local communities in which they work.

Because I have that pain of being in war, and all that, then I feel if I can get that opportunity to join Peace Canal, I will also put my input to change my community from war to some other mutual understandings.

- Stephen Lomeling, Procurement Officer

Unity is another secret weapon - despite having to wrestle as a team with some very real tensions, they continue to choose to stand together in their differences for a greater good.

Every son and daughter of the conflicting communities were together, they were working together and approaching their community together… [The communities] were seeing their daughters and their sons coming to tell them, ‘Enough is enough, you need to talk and find a common ground.’

- Gordon

It’s members of their own families who have been abducted, killed or raped in the decades-long tit-for-tat raids between communities. In the last 3 months of 2023, 406 people were killed in violent attacks, 100 were abducted, 293 injured and 63 were victims of conflict related sexual violence. As we speak, one of the largest mobilisations we’ve seen in recent times is taking place in Jonglei state which is likely to devastate thousands more.

Our team are working every channel available to try to prevent a bloodbath, but grief and revenge has reached boiling point in recent months. There’s a swell of rage amongst these communities, reeling from a spate of recent cattle raids, drowning out the voices of reason.

But over the last four years, the team has built trusted relationships with many of the key players on each side of the conflict and have the ear of the ‘spiritual’ leaders and chiefs, currently leading the charge.

There was a gloomy atmosphere in the glossy, air conditioned conference hall as we discussed the mobilisation. But these guys are dedicated…

Deputy Area Coordinator of Greater Pibor, Lilimoy, shared with me about how he’d recently walked with one of the armed youth leaders in the bush for 2 days straight to build a personal connection with him. Imagine a foreign aid worker doing that… (risk assessment says ‘no’).

…and they’re courageous.

In 2020, one of the organisation’s first acts was to gather the armed leaders from three warring communities to meet in Rumbek - 30 odd tribal militia leaders on charter planes, coming face to face with their sworn enemies. This was something that had never even been considered before, for the risk management headache alone.

The group came out with a peace agreement, and a ‘traditional walking over the white bull’ ceremony sealed the deal. Afterwards, a report stated that ‘conditions are now strengthening for flood affected communities to move to higher ground in previously insecure areas [and] for humanitarian [aid to reach] communities in famine…’

When peace returns to communities, new possibilities emerge.

Who knows what will happen with this current mobilisation - or South Sudan’s first general election, due to take place at the end of the year. But, I sense a good thing emerging with these guys around and their upside-down way of doing peace building. I just hope that we can get the message to spread…

The Pilgrimage of Peace

‘The Pope just waved at me! Do you think he recognised me?’ I shouted through the noise of the crowd.

‘Apparently he has a really good memory’ said Archbishop Justin’s chaplain affirmingly.

I’d been standing at the verge of the red carpet, which cut a long line from ‘Shepherd One’, through the baking tarmac at Juba airport. Huge freshly printed PVC welcome signs bearing Pope Francis’, Archbishop Justin’s and Moderator Ian’s larger than life faces covered the railings, as a flank of battered military trumpets unleashed a fanfare under the hot sun.

This was one year ago this week, when I was a part of the Archbishop of Canterbury’s small entourage for the 3 day ‘Pilgrimage of Peace’ in South Sudan.

‘The Pope just waved at me! Do you think he recognised me?’ I shouted through the noise of the crowd.

‘Apparently he has a really good memory’ said Archbishop Justin’s chaplain affirmingly.

I’d been standing at the verge of the red carpet, which cut a long line from ‘Shepherd One’, through the baking tarmac at Juba airport. Huge freshly printed PVC welcome signs bearing Pope Francis’, Archbishop Justin’s and Moderator Ian’s larger than life faces covered the railings, as a flank of battered military trumpets unleashed a fanfare under the hot sun.

This was one year ago this week, when I was a part of the Archbishop of Canterbury’s small entourage for the 3 day ‘Pilgrimage of Peace’ in South Sudan.

I’d met the Pope four years prior on a previous trip with the ABC to the Vatican. The Vice President of South Sudan, Riek Machar had, by then, been in hiding for five years, following an outpouring of violence in the capital, when forces loyal to him and those loyal to President Salva Kiir had turned on one another. Archbishop Justin had sent a team to reach out to Riek Machar and managed to convince him and the President to meet in the Vatican to work out their differences. It was on this famous occasion that the Pope had knelt down, through the pain of arthritic knees, to kiss the feet of the two leaders. In the days following that historic meeting, Riek Machar was peacefully reinstated as First Vice President.

I was at the Vatican in 2019 and now in Juba to help rebuild confidence in the South Sudanese Peace Process and to cast light on the incredible unseen work of the global Anglican Church and its affable leader. This is what I do for my work - I tell stories and produce creative campaigns that help to restore trust between organisations, or institutions like the church, and the public. The problem is that people don’t often seem to want to know about the good stuff. Stories that affirm the church as harmful or irrelevant make for much more satisfying reads.

In the week leading up to the ‘Pilgrimage of Peace’, the newspapers were hot with scandal about our South Sudanese host, Archbishop Justin Badi Arama. He had publicly stated that the church of South Sudan would likely decide to renounce his namesake and boss as leader of the Anglican Communion.

Archbishop Badi wears an upside-down smile, but his eyes are kind and discerning. On our arrival at the Episcopal guesthouse, the team prayed together with him in his office. His voice was soft and sincere as we petitioned God for peace. Throughout the trip, the Archbishop Justins were together frequently. They were brotherly and respectful and clearly both loved the Anglican Church as their own.

On the 2nd day of the tour, between 50,000 and 70,000 South Sudanese gathered in the John Garang Mausoleum - Juba’s vast and dusty outdoor arena, which has the appearance of the remains of an ancient Olympic stadium cast in concrete. Many had walked for days to be there and they were about to witness the first prayer service ever to be jointly hosted by the heads of the Catholic and Anglican churches in their 700 year history.

As a Catholic nun said to me the morning after, hushed and sweet with a spiritual hangover, ‘No political leader in this country could rally 70,000 people willingly, walking through the night, not sleeping for two days to attend this spiritual event. Nobody talked about which tribe will enter …no they just come from all languages and all corners.’

In a country that has experienced an estimated 400,000 deaths since 2013 from internal conflict …and in a world where the Catholic-Protestant wars throughout history have led to millions of other lives being lost, this was good news.

Being a part of this may be the greatest privilege I will ever have. We had good global coverage and made the headlines in most of the UK’s major news channels. Within a week of our return, though, the noise of scandal returned to drown out the good news again. Weeds amongst wheat.

Working to build public faith in the church can be disheartening at times, but there are always reasons to keep going. Here are four that keep me going:

Without hope and trust there is only chaos. What else would we do?

Every human organisation is imperfect and often scandalously hurtful, but that’s rarely all they are. Positive stories give us the imagination to work towards something better, whilst shaming the people who seek division and destruction.

Despite the media’s appetite for it, scandal and conflict never has the final word. Often those in conflict are the ones who love the thing they’re fighting over the most. Good conflict can resolve in healing and hope.

Popularity comes and goes, but credibility is the most important thing. Credibility is established over a longer period of time, often through unremarkable actions that go under the radar. But then sometimes great acts of hope burst through the surface: Popes kissing the feet of warring leaders; or once warring religious leaders leading multitudes in prayer for unity in war-torn countries.

When those stories emerge, we are here to tell them.